White Guilt and America's Paternalism

One more way ideologues grabbed hold of our beloved institutions

**Below is an essay for my English class that I found to be politically relevant, and have thus adapted for publishing in this publication. For reference, the prompt was: “how has settler colonialism and America’s legacy of white supremacy impacted your humanity?”**

In the wake of the racial reckoning in the years following the ‘summer of love’ in 2020 and the death of George Floyd, it seems that race has constantly been at the forefront of any and every conversation in the halls of academia and her departments of humanities. It is unavoidable for the average college student in the year 2025 to avoid the topic. By now, most students have been exposed to these ideas since middle school, and I am certainly no exception. However, it seems as though teachers, professors, and educators alike are far more focused on the ideology of their various claims about racism, settler colonialism, white supremacy, oppression, and the like than they are about any sort of reality that is linked to such ideas. This is certainly not for lack of trying on their part, but the fact remains that no such realities exist, and any attempt to forge one becomes more and more antiquated with each passing year. These ideas may have been fresh and exciting in the 1990s, but with decades of hindsight, it’s become increasingly clear that these ideologies are exactly that, and nothing more. This is not to say that racism and oppression do not or have not ever impacted humanity, but simply that the attempt to tell a tale of a broad ideological grand theory of oppression that permeates American history is fantasy and historical revisionism. This is no more true than it is with the teachings of settler colonialism. In my case, settler colonialism strictly as an ideology, has affected my humanity far more than it has as a practice. This is because in order for it to work, it requires a belief in rigid oppressor/oppressed moral binaries that simply do not reflect my lived experience, and objective truth. These frameworks, as examined through Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s paper: Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor (pp. 1-40) and Rudyard Kipling’s poem The White Man’s Burden reveal that this ideology relies on this binary, and cannot accept any nuance or individual personal agency. Through this essay, I will examine the ways settler colonialism as an ideology has affected me, and how as a practice it has not at all.

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s 2012 paper insists on some bizarre notion not only of collective guilt, but of perpetual oppressor and oppressed binaries. The pair dismantle the metaphorical appropriation of decolonization in educational discourses, arguing that it must remain a literal, land-centered process of repatriating indigenous territories and disrupting what they call settler structures.

“Decolonization in the settler colonial context must involve the repatriation of land simultaneous to the recognition of how land and relations to land have always already been differently understood and enacted; that is, all of the land, and not just symbolically.” (Tuck & Yang 8)

Their core claims reveal settler colonialism as an enduring structure, and not a past event, predicated on the “disappearance” of indigenous peoples and the entrenchment of settler supremacy through an entangled triad of settler-native-slave dynamics.

“Everything within a settler colonial society strains to destroy or assimilate the Native in order to disappear them from the land… these desires to erase–to let time do its thing and wait for the older form of living to die out, or to even help speed things along (euthanize)...these are all desires for another kind of resolve to the colonial situation, resolved through the absolute and total destruction or assimilation of original inhabitants.” (Tuck & Yang 9)

Non-indigenous individuals, regardless of race, are positioned as inherent “settlers” bearing collective moral responsibility until land is returned, a binary that flattens individual agency into inescapable complicity.

“Settlers are diverse, not just of white European descent, and include people of color, even from other colonial contexts.” (Tuck & Yang 7)

Finally, the duo strike the core of their critique by placing the blame entirely on the descendants of the colonialists and insisting that they bear and perpetuate the sins of their forefathers. This introduces the idea of perpetual guilt brought about by this position.

“Settler moves to innocence are those strategies or positionings that attempt to relieve the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land or power or privilege, without having to change much at all... These moves ultimately function to re-entrench the settler project.” (Tuck & Yang 10)

Now here’s where I think the two are on the right track– there absolutely is a heavy dose of guilt that progresses this ideology; however, the blame is misinterpreted. The predominantly white “settlers” feel guilty not because they feel the weight of their ancestors’ sins, but instead because they do not want to be perceived as racist by the academia crowd like Tuck and Yang. In his 2006 book: White Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed The Promise of The Civil Rights Era, Shelby Steele, a Black scholar and fellow at the Hoover Institution, defines “white guilt” not as individual remorse for personal sins but as a structural loss of moral authority for whites and American institutions stemming from the civil rights era’s reckoning with historical racism.

“I know it to be something very specific: the vacuum of moral authority that comes simply from knowing that one’s race is associated with racism. Whites (and American institutions) must acknowledge historical racism to show themselves redeemed of it, but once they acknowledge it, they lose moral authority over everything having to do with race, equality, social justice, poverty, and so on. They step into a void of vulnerability. The authority they lose transfers to the “victims” of historical racism and becomes their great power in society. This is why white guilt is quite literally the same as black power.” (Steele 24)

This guilt manifests as a pervasive stigma—whites are reflexively branded as racist, prompting dissociation from their own power and heritage to “prove” innocence. Steele argues it fuels patronizing, race-based policies, like affirmative action and diversity mandates, that treat minorities as perpetual victims needing uplift, rather than agents capable of self-reliance. This creates a “racial spoils system” where racism becomes exploitable “currency” for leverage, that erodes personal responsibility. Steele sees it as self-destructive: it emasculates white moral agency, infantilizes minorities, and undermines the civil rights promise of equal responsibility, leading to cultural stagnation and distorted humanity. This is reflected entirely in my personal experience. This invention by figures like Tuck and Yang constructs a totalizing ideological identity—“settler”—that overrides individual agency or moral diversity. When in fact, I had absolutely nothing to do with any of the circumstances I was born in. Furthermore, while I may enjoy certain relative advantages today, this framework denies the basic reality that many “settler” descendants remain mired in modest circumstances, far from the mythic prosperity supposedly harvested from centuries of oppression. All four lines of my family have been here since the 1600s, yet nobody in any one of those lines has amassed any generational wealth or land. Both of my parents are first generation college graduates. One might think with a multi-century head start and a legacy of oppression, my “oppressor” ancestors might have played the game a little better. This is why when I sit, as I have many times this semester, in a college class where professors frame present-day America as an ongoing colonizing project and imply moral responsibility for historical wrongs solely based on ancestry, I simply cannot believe them. Many students may buy into this narrative, feeling pressure to accept a predetermined moral role that does not match their actual experiences or behavior, which is what actually perpetuates the lie. This ideology, as a result, has impacted my humanity far more than any legacy of racism will ever.

I’ve examined how white guilt constructs contemporary racial divides, but the seeds of this ideology reach much farther back. Ironically, English poet Rudyard Kipling displays the same dim view of human agency in his racist poem The White Man’s Burden. Instead of assigning guilt, Kipling takes the opposite approach and assigns paternalism to the colonizer, and infantilizes the colonized.

“Take up the White Man’s burden—

The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch Sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.” (Kipling, Stanza 3)

This highlights the colonizer’s heroic toil undone by the “Sloth and heathen Folly” of the colonized. This patronizes the colonized as lazy, heathen obstacles, removing their agency, and forces the colonizer to assume the paternal role of caretaker, simultaneously removing their agency. As such, Kipling argues that civilizational progress depends on external intervention, not internal capability.

“Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.” (Kipling, Stanza 1)

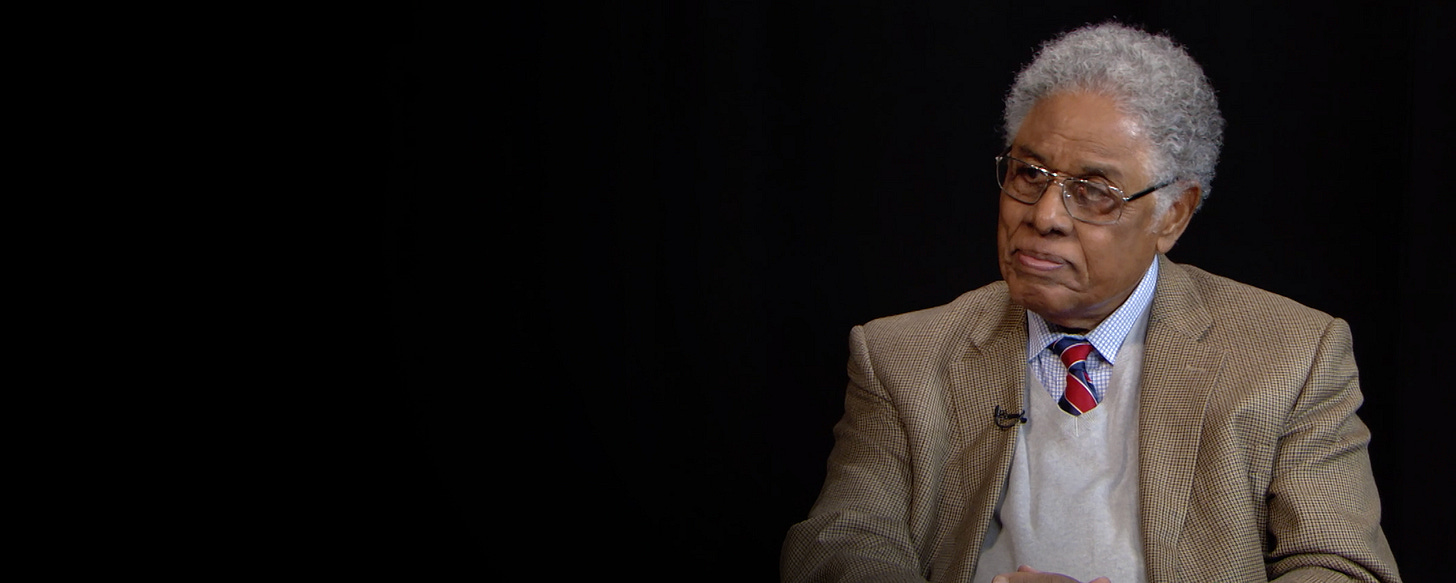

This is the core infantilization: the colonized are pitched as a hybrid “child” (innocent but wild or devilish), implying their inherent immaturity requiring paternal “binding” and “exile” from the white man’s “best ye breed.” This further denies their agency, framing them as captives needing service. Black economist Thomas Sowell frequently critiques paternalism as a condescending elite impulse, rooted in self-congratulatory “visions” of social engineering, that assumes the inferiority or helplessness of marginalized groups, leading to policies that undermine self-reliance and agency. In his 1995 book: The Vision of the Anointed: Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy, Sowell attributes this paternalistic behavior to those he calls “the anointed”: a self-perceived elite class of intellectuals, academics, journalists, and policymakers who promote social policies driven by a moralistic “vision” rather than empirical evidence or practical outcomes.

“The vision of the anointed is one in which such ills as poverty, irresponsible sex, and crime derive primarily from “society,” rather than from individual choices and behavior. To believe in personal responsibility would be to destroy the whole special role of the anointed, whose vision casts them in the role of rescuers of people treated unfairly by “society.” Since no society has ever treated everyone fairly, there will always be real examples of what the anointed envision. The fatal step is to make those examples universal explanations of social ills-and to remain oblivious to evidence to the contrary.” (Sowell 203)

Sowell argues the paternalism of the anointed masquerades as compassion but serves ego and power, creating dependency while ignoring empirical outcomes. This mirrors Steele’s “white guilt” as a stigma eroding moral authority, driving patronizing “reforms” that infantilize minorities as perpetual victims. Both see it as distorting humanity. Sowell’s analysis provides empirical ballast to Steele’s psychological framing, showing how paternalism perpetuates the very disparities it claims to fix, much like guilt-fueled binaries in settler discourse promote predetermined roles. In other words, Tuck and Yang’s paper and Kipling’s poem are two sides of the same, un-nuanced, ideological coin. This coin erodes my humanity personally, as well as humanity at large. When institutions like universities impose an identity narrative on students, it impacts their humanity by restricting their agency and self-determination. I feel pressure to conform to this narrative since I don’t want to argue or speak out, so I have to sit quietly and take it. This leads to corrosion and is the exact opposite of the supposed mission of education universities promise their students. This isn’t education, this is religion.

Settler colonialism, the ideology, has impacted me deeply. Settler colonialism, the practice, has not. I’ve examined this stark dichotomy through two frameworks: the guilt narrative of the Tuck and Yang paper, and the paternalistic narrative of the Kipling poem. Both seek to advance the same thesis: that humans are broadly and fundamentally guided by animalistic hierarchies and have no agency. Neither have any solution that is politically or logically feasible, mostly because their presuppositions are completely unsupported by reality. It’s far more tempting to pin our struggles on some sweeping sociopolitical narrative than to own our choices or the roll of the dice in life. Instead, I advance a better path forward: one that shrugs off the weight of inherited guilt and the smug hand-holding of paternalism. My lived experiences don’t confirm the narratives pushed by the anointed. If anything, they show the ideological and manipulative nature of these frameworks. Ultimately, what threatens my humanity is not historical injustice, which I acknowledge as real, but an ideological framework that assigns me a predetermined role and denies the legitimacy of my individual experience. The true task of preserving my humanity requires rejecting imposed narratives and thinking freely, not adopting predetermined roles dictated by ideological systems.

Works Cited

Kipling, Rudyard. The White Man’s Burden. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday & Company, 1899, www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poem/poems_burden.htm.

Sowell, Thomas. The Vision of the Anointed : Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy. New York, Basicbooks, 1995.

Shelby Steele. White Guilt : How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights Era. New York, Harper Perennial, 2007.

Tuck, Eve, and Yang, K. Wayne. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1-40.