Losing the Heartland: How a Madison County Field Became a Battleground for Ohio’s Future

From family farm to solar frontier, Madison County’s land tells the story of Ohio’s struggle between heritage and progress.

Just five miles north of London, Ohio, a 6,000-acre farm with nearly a century of history has become the center of local controversy, including plans for the nation’s largest solar panel farm.

In 1933, Mary Johnson purchased a parcel of land, named it Orleton Farms, and began producing farm products to sell—eggs, milk, cream, and corn, among others. If you ask most Madison County natives, they can point to the Orleton Farm on a map and can tell you at least a portion of its history.

In 2007, the van Bakel family, who owned the property at the time, proposed building a 5,400-cow dairy farm—an idea that quickly alarmed residents. Environmental advocates from the Darby Creek Association cautioned that “the land drains to Bales Ditch and Chenoweth Ditch, which flow to Spring Fork, which then flows into the Little Darby Creek.”

The dairy farm would’ve had numerous benefits. According to an early 2008 Columbus Dispatch story, the farm would’ve employed 35 people, would’ve helped reduce the ‘milk deficit’, and would’ve paid taxes. That doesn’t underscore the issues and community opposition, but does show that there would have been some benefit to the local community despite concerns.

Nevertheless, the group abandoned the dairy plan, and Midwest Farms, LLC, purchased 6,001 acres of prime Deercreek, Somerford, and Monroe Township farmland for $27.1 million at auction on June 30th, 2009. Midwest Farms, LLC., is a landholding company owned by tech billionaire Bill Gates. The Darby Creek Matters organization said to the Dispatch that they would be happy if Gates were the new owner, because of his interest “in enhancing agriculture and food production in developing countries to combat hunger”. They saw it as a positive sign that he would keep the land as a farm.

Fast-forwarding to September 2022, Madison County zoning permits large ground-mounted solar projects, and over 9,300 acres of land are already being used for, or planned for, mass solar projects. Savion Energy, a subsidiary of Shell Oil, was already constructing a solar project in Madison County. Madison Fields Solar, a roughly 2,000-acre project on leased land near Rosedale, was approved in January 2021 and was under construction.

Savion Energy officially files a new application for a 6,000-acre solar farm named Oak Run Solar Project. The Oak Run Solar Project would be the largest solar farm in the nation and, in partnership with Ohio State University, would introduce crop farming and livestock within the panels. Oak Run is the first project of its kind.

Residents opposed this project, as many feel Madison County is becoming oversaturated with solar. It is well known that the county is a longtime agricultural community. Amid new housing developments, solar projects, and warehouses, many residents worry that they are losing their agrarian heritage.

Despite almost unanimous opposition from county residents and elected officials, now-former County Commissioner Mark Forrest (R-West Jefferson) supported the project, saying to Midstory, “I feel it is my duty to do what’s best for all the residents of Madison County. Allowing Oak Run to be permitted would be advantageous for the taxpayers of our county.” He was the first to testify at the Power Siting evidentiary hearing in 2023.

Two local school superintendents have vocally backed the project, pointing to the promise of new tax revenue for their districts. Notably, Jonathan Alder Schools covers most of the 6,000 acres, and did not make a statement.

Former State Senator Stephanie Kunze came out in support, even though she never faced an election in Madison County during her time in the statehouse—and was rejected by local voters in her 2021 run for Congress.

Madison County residents spoke out often against the proposed projects at community events, town halls, and online through social media and the official Power Siting Board public comment forum. Despite this, Commissioner Forrest maintained his support of the project throughout the 2024 primary election. On March 19th, Madison County voters finally had a chance to make their voices heard at the ballot box.

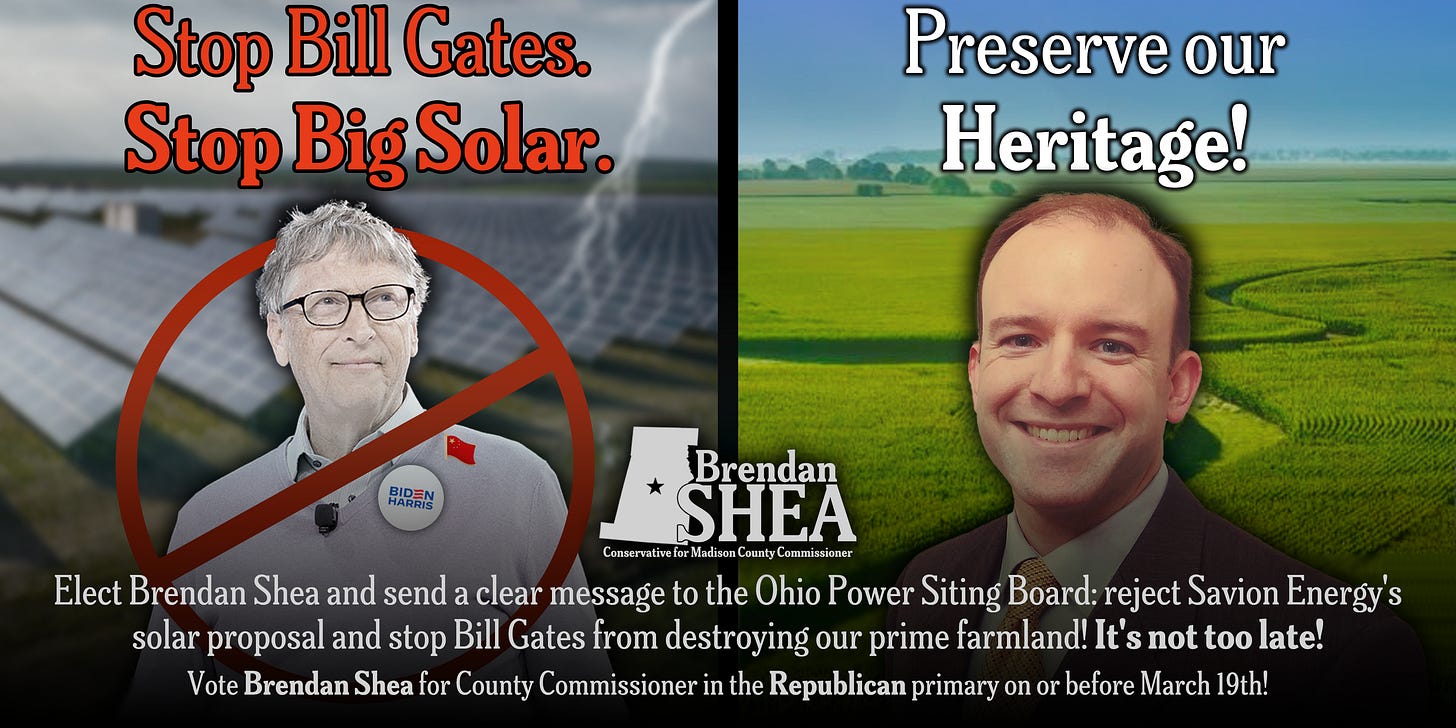

During the 2024 Commissioner primary election, Forrest was running for his fifth term. He was challenged by former local school board member and village councilman Cory Coburn (R-London), who ran a campaign on standard conservative issues (though he later gravitated toward an anti-solar message), and State Board of Education member Brendan Shea (R-West Jefferson), who ran a campaign entirely rooted in solar opposition and worries of degrading the county’s agricultural heritage.

To say Madison County voters spoke would be an understatement. Despite numerous mailings showing conservative credentials, Forrest lost the election, receiving only 21% of the vote. Coburn received 18%. Voters resonated so strongly with the anti-solar messaging that Shea won 57.5% of Madison County voters, defeated the pro-solar incumbent, and restored unanimous local elected opposition to Oak Run Solar. Candidates who were openly anti-solar received three-fourths of the votes in the Republican primary, and no other candidate mounted opposition to the nominee, Shea, in the general election.

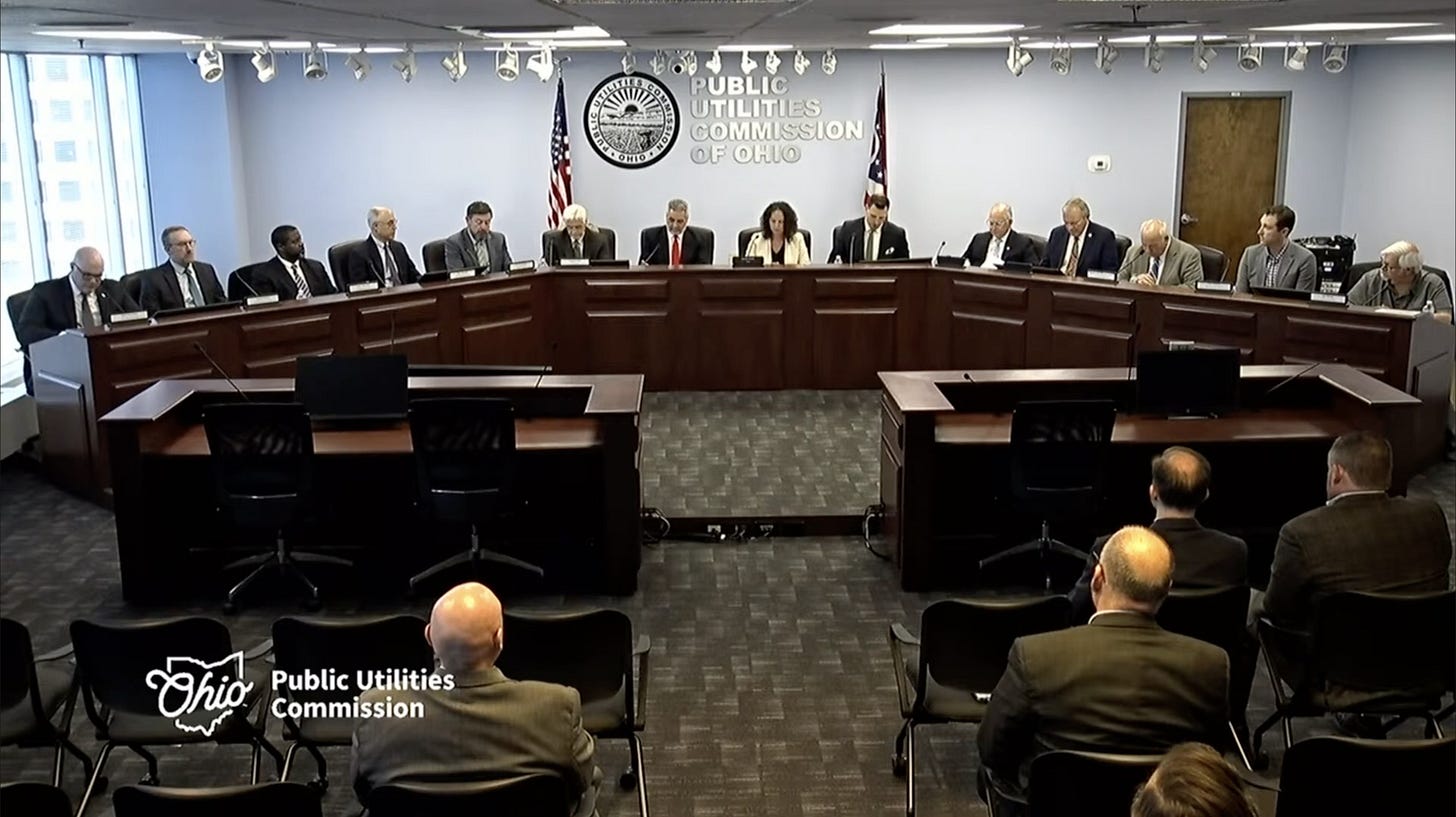

Commissioner Chris Wallace (R-Plain City) served as Madison County’s ad hoc board member during the March 21st hearing of the Power Siting Board, and he stated, “if this board is to approve this project, they would be doing so in the face of strong local opposition, I think spitting in the face of Madison County voters”.

Township Trustee Jim Moran (NP-Somerford) served as the ad hoc member for the three townships and noted the unanimous opposition of Madison County township trustees, both directly and indirectly affected by the project.

Despite the landslide election statement and dissenting votes from both of Madison County’s representatives, the Power Siting Board voted to approve the project, citing support from a State Senator and a Commissioner, though they did not name them. The vote was almost unanimous—the county elected officials were the only two ‘no’ votes.

Madison County Commissioners unanimously voted to apply for a rehearing on March 26th, and on April 19th, 2024, attorney Jack Van Kley entered the application. The Power Siting Board denied that application on August 22nd, 2024, in a 7-1 vote (with ad hoc member Wallace casting the only ‘no’ vote).

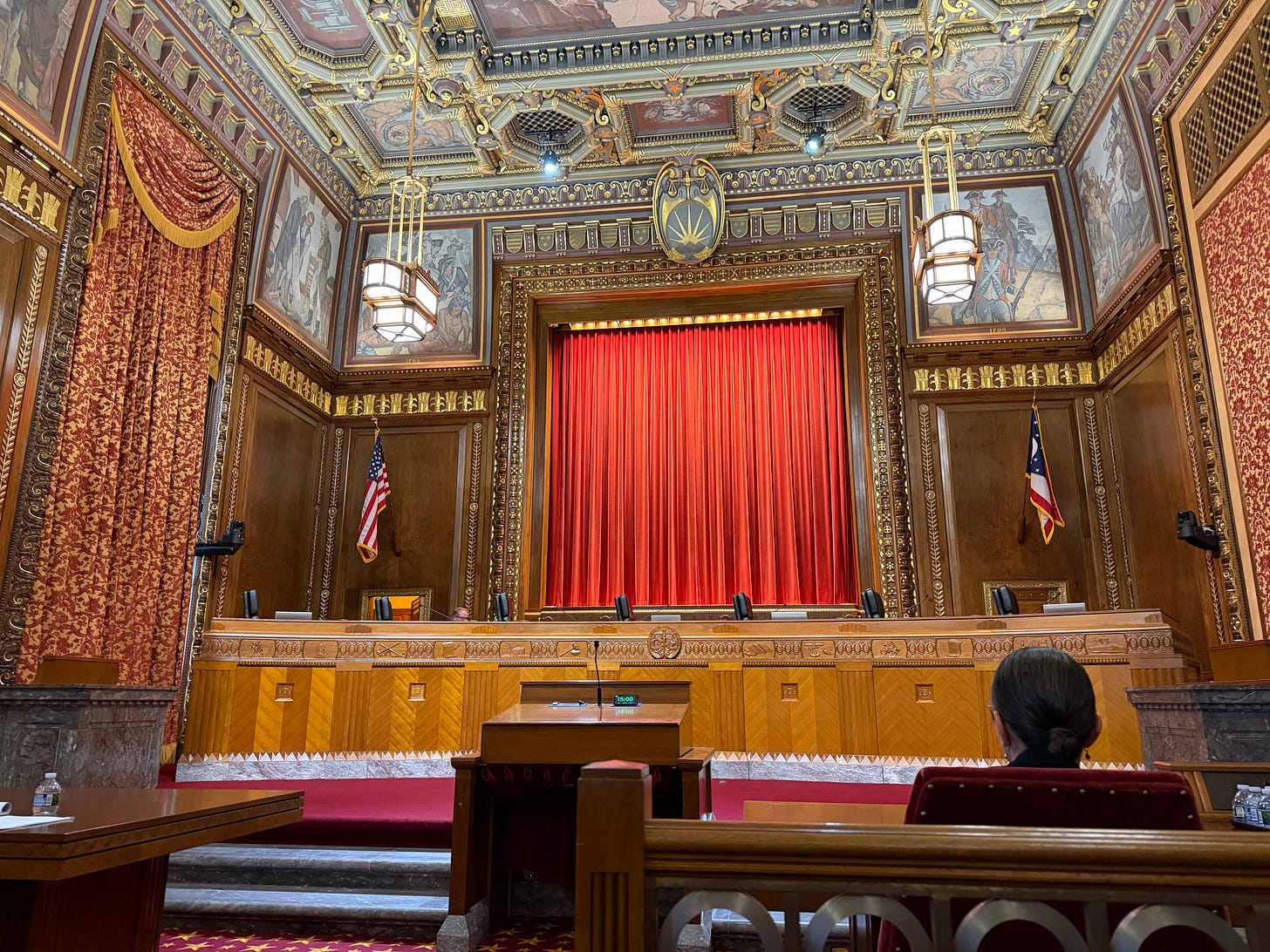

In late October 2024, Madison County and local townships filed an appeal of the decision to the Ohio Supreme Court. The court held oral arguments on October 28th, 2025. You can watch the hearing and make up your own mind here, but it would be an understatement to say state attorney Ambrosia Wilson came unprepared and did not make an excellent argument for their side.

Van Kley, attorney for Madison County et al., stated that the official record lacks multiple types of documentation required before approval. The missing documentation includes water-sampling surveys, firefighting plans, and substation simulations. Wilson implied that water surveys were not needed because there was no aquifer. Despite Wilson’s claim, the land drains to Little Darby Creek, as highlighted earlier.

Freshman Justice Dan Hawkins (R-Columbus) questioned Ms. Wilson and echoed the sentiment of many county residents.

“This is the largest and first of its kind of these projects in the nation, correct? And it seems like we’re hearing about some missing items here and there. There’s obviously substantial pushback from the people who live in the country around this area, but I get the sense at the Power Siting Board that it’s almost being treated like they’re putting up a windmill. Don’t you think there should be some extra steps to make sure, like the Chief Justice was asking for with the water safety plan and the fire safety plan? I would think the siting board should maybe have gone sort of above and beyond, provided some of these other materials, some of these things that are missing, because one of the things you’re supposed to consider is the impact, the public interest, convenience, and necessity of the community. I would think instead of just saying, well, we’re not required to ask for that stuff, that maybe you do for a project this large.”

- Justice Dan Hawkins (R-Columbus)

The Supreme Court has never overturned the Power Siting Board’s decision on a solar certificate.

As of 2025, all Madison County elected officials who have spoken on the issue are opposed to this project. Commissioners Wallace and Dr. Tony Xenikis (R-London) voted in March of 2023 to reject the project. The Madison County Township Association is unanimously against the project. State Representative Brian Stewart (R-Ashville) and State Senator Michele Reynolds (R-Canal Winchester) are Madison County’s Statehouse representatives and have both filed comments of opposition. No elected officials currently serving have shown support for the project, which would meet the criteria for unanimous local opposition.

Now, concerned residents and clean energy advocates are both awaiting a decision from the state’s highest court. There is no set timeline for when that decision will be released.

The Supreme Court’s decision will echo far beyond Madison County. A ruling to uphold the Power Siting Board will set a precedent that state agencies can bypass community consent and required procedures whenever it’s convenient. But a reversal would reaffirm that Ohio’s Constitution still protects local interests and that rural citizens still have a say in their destiny.

This isn’t an issue of private property rights; that claim is null and void when out-of-state ultra-billionaires spend tens of millions of dollars—money the current landowners cannot refuse—to buy or lease prime farmland and take it out of production. This is an issue of the degradation of our nation’s food supply so that major corporations can get tax credits for ‘green energy’.

The stakes could not be higher for Madison County and for every Ohioan who believes their land and their voice still mean something. What’s happening here isn’t just a local dispute, it’s a test of whether we still value the principles that built this country: self-reliance, stewardship, and respect for the working land that feeds our people. When vast tracts of productive farmland are transformed into industrial solar zones, not because communities chose it, but because powerful investors decided it from afar, it strikes at the very heart of what it means to be American.

Our founders built this nation on the belief that freedom and ownership come with responsibility to one another, to the land, and to future generations. To let corporate greed and government incentives override the will of rural communities is not progress; it’s a betrayal of those founding ideals. It’s un-American to strip citizens of control over their local landscape, to silence their opposition, and to prioritize profit over people, power over principle, and short-term gain over the long-term future of America’s heartland. And it’s un-Ohioan to undermine the independence and integrity of local citizens who only ask to be heard.

What’s unfolding across Madison County isn’t progress; it’s a slow erasure of Ohio’s identity, its values, and the spirit that has always defined who we are. ■